This Thing Does Not Scale

Reflections on 20 Years of Working Without a Net

Twenty years ago this month, I left my last job with a regular paycheck and benefits. A former employer offered me a long-term freelance writing opportunity as a subcontractor to NASA. I had some experience with the agency, and I’d found the work challenging and the people passionate about their mission. In short, it looked like a beachhead that would provide some stability while allowing me to build a solo practice. I gave notice to the nonprofit organization that didn’t have quite enough work to keep me busy and said my goodbyes at the holiday party.

I also had a passion project with a couple friends that had yet to yield a nickel. We were three frustrated speechwriters trying to crack the code of public speaking. What made some speakers great and others lackluster? It wasn’t just about the words, because each of us had each written good speeches that had fallen flat and vice-versa. We were captivated by the social science of nonverbal communication popularized in Malcolm Gladwell’s Blink, particularly the concept of “thin slicing,” which refers to how people make snap judgments about each other.

We immersed ourselves in the social science literature and helped fund a research project run by a couple of economists who were interested in the same questions that intrigued us.

We did free coaching for friends who wanted it, and began to cobble together a training methodology based in both theory and practice.

A year later, the side hustle had helped a longshot candidate for Congress dethrone a thirteen-term incumbent, and it had won a name-brand corporate client. Amy Cuddy of Harvard Business School wrote a case study about our coaching methods with the Congressional candidate. KNP Communications was legit.

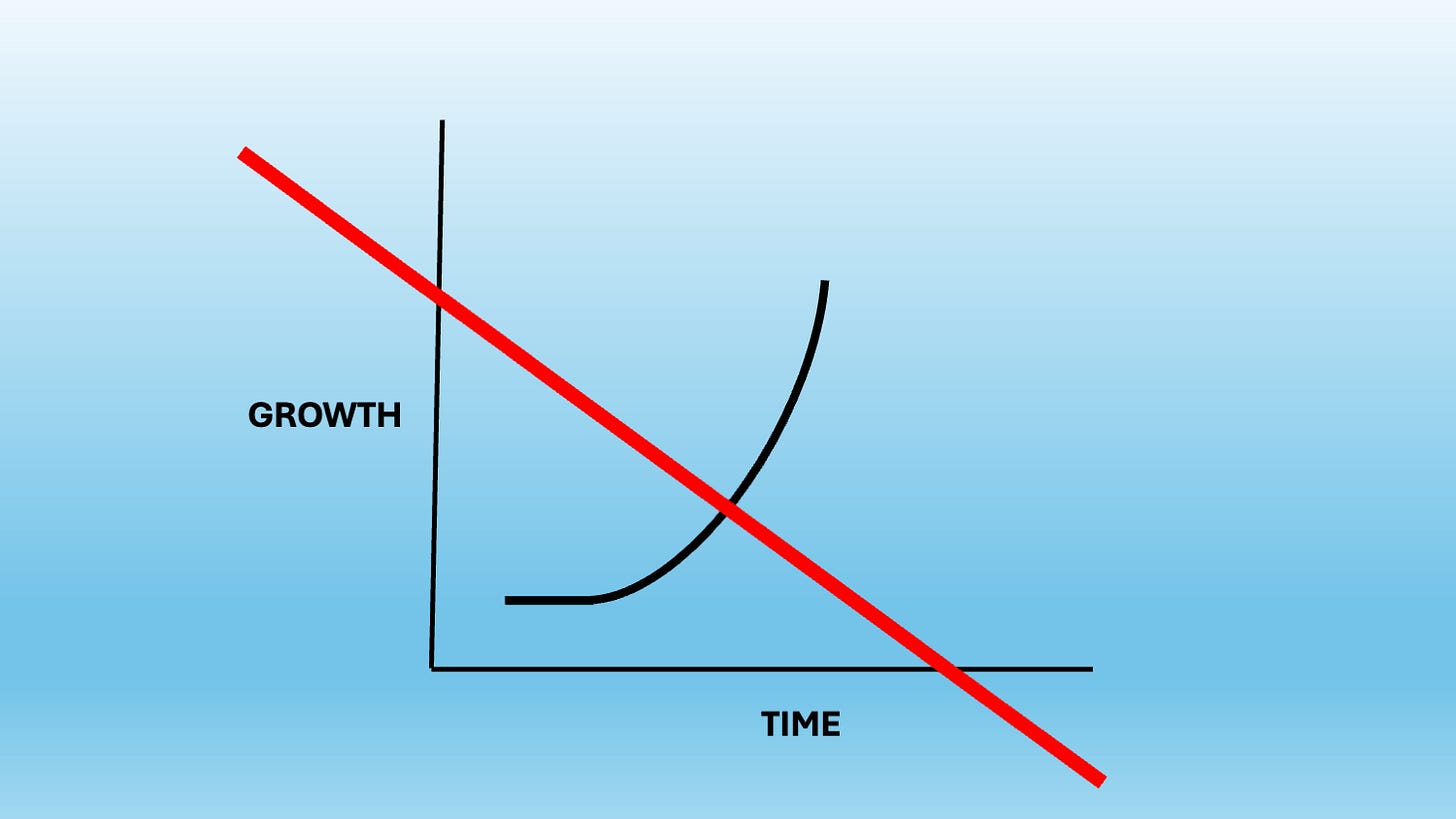

It still took a few years until KNP brought in enough business to crowd out the writing work with NASA, and a few more years until we were busy enough to bring in additional coaches beyond the three co-founders. Our growth was gradual, organic, and almost exclusively based on word-of-mouth referrals. I served as the managing partner, which meant tending to janitorial duties like contracts, insurance, business registrations, and payments.

We did none of the things that a startup should have done to position itself for rapid growth that would lead to acquisition. We didn’t have an office or employees. (This is nothing special today, but a dozen years ago it raised eyebrows about credibility.) We didn’t hire young, cheap associates to work with clients so we could focus solely on growing the business. Instead, we built a diverse team of subcontractors who were experienced and credible with clients from Day 1, and we paid them well and trusted them to run their engagements. We hired lawyers, actors, nonprofit executives, refugees from the corporate world, and a women’s lacrosse referee, all of whom shared a passion for helping our clients become outstanding communicators.

Along the way, we talked to smart people who advised us on various ways to expand, and we took their counsel seriously. We wrote books and talked to the media and marketed ourselves a dozen different ways, but our internal recordkeeping kept telling the same story: word of mouth was overwhelmingly our most powerful source of new business.

We decided that was fine. The goal was not to get acquired so we would have to answer to a new boss. We liked working with our clients. When we realized it was time to think about succession planning and decided to bring in new partners, we looked to colleagues who had worked with us for a dozen years and knew our methods and modus operandi.

Twenty years in, I’ve learned a few lessons about working without a net.

Say goodbye to normal hours. This is no great secret, but it’s worth thinking hard about before cutting the cord to steady employment with a routine schedule and paid time off. For nearly a decade I worked 8:30-5:00 followed by an hour or so after dinner and then a late shift of 2-3 hours. I quit the late shift a long time ago, but I still answer emails until 8 pm, work weekends as needed, and take an occasional evening call.

The business cycle ebbs and flows, but the insecurity never goes away. After two decades that included the Great Recession, the pandemic, and a handful of government shutdowns, I’ve experienced enough contractions and expansions to know that they end. Even so, an abundance of white space on the calendar still leads to doubts: is this time different? The only things I’ve found that help during the slow times are a regular schedule and plenty of exercise.

Response time is critical. Whether it’s a new prospect or an old client, speed matters in a world in which potential clients are juggling dozens of priorities. A quick email response to a fresh inbound lead can sometimes spark a back-and-forth that breaks the ice even before an intake call. Similarly, when someone hands me a business card at a conference, following up with a short note the same evening goes a lot further than waiting until the flight home. Attention breeds conversions.

Let clients know that you’re thinking about them even when you’re not on the clock. One of the challenges of doing one-off engagements is that you fall off the radar when the gig is done. Part of my marketing energy goes into sharing ideas with past clients when I come across an article, video, or podcast that will interest them. I don’t do this exclusively to stir the pot for business development; I do the same thing with friends.

No assholes. This was the first explicit rule of KNP, and it goes for clients as well as colleagues. Life is too short.

When I quit my last job, my colleague Carl warned that I’d go crazy after a couple months of staying home and working for myself. I respected his judgment. Part of me worried that he might be right. Carl, thanks for your concern. It turned out okay.

Great lessons! I especially like this one, which I have also employed, with more or less attentiveness. "Let clients know that you’re thinking about them even when you’re not on the clock."